Event details

Extensions of a collapsing landscape, intubated futures

Maryam Khosrovani & Kaveh Irani

May 13 - June 10, 2023

Opening reception: Saturday, May 13, 4:00 - 8:00 pm

Kaveh Irani and Maryam Khosrovani are both visual artists who studied arts in Iran before moving abroad and becoming part of the “diaspora”, relocated throughout the United States and Europe. They were already active around the turn of the 2010s, and the peak in the internationalization of “Iranian contemporary art”; an intense period of calls and opportunities provided by Western institutions to Iranian artists. While the years of the 2010s saw the rise of a speculative and unstable Iranian art market – as Iran itself could be – it eventually led to worse; with the years of Donald Trump's presidential mandate. Economic depression, reduced mobility and post-diasporic rupture then became the rule for a majority of Iranian artists – in and out their homeland. To quote the artist Nil Yalter: “Exile is a hard job”. Kaveh Irani and Maryam Khosrovani, who developed their core practice in this conflictual context, are from a generation who understood displacement and transitional spaces as not temporary but rather permanent; a generation who experienced the dark days of globalization, or its conservative and at times racist backlash; a generation who is often challenged in its physical movements and travel conditions, running out the (time of the) present, envisioning “intubated futures”.

Unlike a vast number of Iranian artists highlighted since the years 2000 on the international scene, Irani and Khosrovani work against the grain of identity politics and Iranianness; one rarely observes orientalist imagery (rugs, miniature and birds), ayatollahs caricatured or veiled fashionistas in their works. They rather cultivate a kind of distorted minimalism, more influenced by the infrastructure of globalization (and non-verbal communication tools) than its dreamed representations and touristic visions. Their Iranian experience, language and background remain active, but it plays more as a conceptual or philosophical spectrum than an identity pattern or commodity. The captivating dialogue conveyed by their reunion; a similar sense of ironic distance with identity issues and their own “transitory” condition, make these two artists emblematic of a new path or phase – post-exotism, post-exile, post-internet.

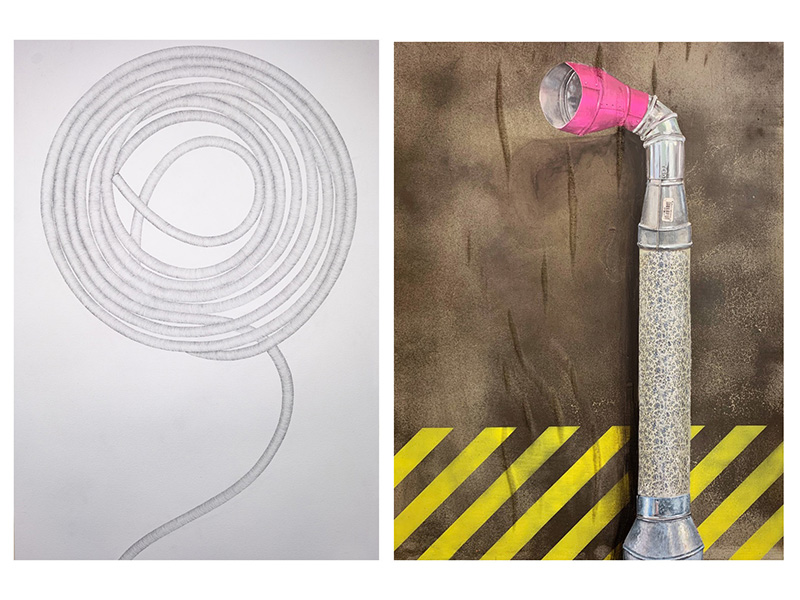

Maryam Khosrovani’s drawings (which at times can integrate weaving, folding, or pinholes) are challenging for the eye. They often playfully unfurl in series and sequences based on kinetic protocols and gravity laws. Her abstract hoses (connected to nothing in particular apart from themselves) and restless whirlpools, with their agility to cause us dizzy visions, appear at first glance as a conceptual art tool synthesizing time, space and body movements in one (transmutable) pattern or language. Behind their minimalistic claim for serendipity and profound stimuli for free movement and improvised directions, Khosrovani’s drawings elegantly attenuate the painstaking hours (days and nights) of work invested in shaping the infinitesimal veins and tubal ligations of the hose. Hence the positions taken by it and by Khosrovani’s work feel as much physical as conceptual.

During the preparatory process, photography plays a key role, as a capsule of the infinite contortions and squirming in which the hose consumes and animates itself; even though Khosrovani works simultaneously from mechanic reproductions and “real life” movements of the “plastic snakes”. The flawless photographic memory (and the overlap of multiple smaller preparatory drawings) encapsulated in the trials and tribulations of the hose somehow survives in Khosrovani’s both hyperrealist and abstract techniques. Her pencil becomes a seismographer that captures the unpredictable moves and circles of a seemingly non-human force (potentially constrained by human influence or technicity but taken out of our sight).

The ambivalence of the hose, as an “anti-form” physical object and an unseizable designed pattern, goes with its psychoanalytic (and even sexual) interpretations; which could be well explained by an original break or rupture in which the hose becomes fundamentally divided: between a subject and an object of desire, between giving and receiving (going in and going out), between taking shape and losing shape; feeling apart in the very act of coming together or finding his/her own or other half. But this psychoanalytic ambivalence actually doesn’t cover the entire subconscious territory of the migrating hose (framed/zoomed in and out).

It can be extended to the deeply personal childhood memory of the typical Tehran garden or courtyard, where the artist (and every Iranian child) used to play with that hose. The drawings also record the incarnated and “tactile” memory of that specific plastic, quite rigid, and difficult to unfurl in a straight line. They bring back an almost physical battle for the child, confronted to a formless and unseizable plastic animal, escaping the hands of the child by its endless and fierce twists.

Eventually, the entire extent of the fundamental visual ambivalence, felt in the formless and infinite shapes of one physical pattern and protocol, also comprises the contemporary political connotation. Nowadays, such forms, beyond their bold erotic potential, playfulness, and optical stimulation, cannot but remind us of the highly political metaphor of the “cables” running our globalized digital economy. Beginning with the submarine cables routes, made for controlling the cloud memory, entailing a transborder data war and mutual surveillance between the powers of the United States, China, and others...

As a matter of fact, the infinity and serendipity of interconnectedness and channel-making that fuel Khosrovani’s drawings invade our stable subjectivity. Hence they spread out beyond the lines of personal traumas and intersubjective reconciliation or those of a self-centered and decentered visual system. They are reversible like a glove that can be worn from the inside or the outside, providing two different identities – always an overwhelming (beginningless, endless) dance.

Kaveh Irani’s paintings of industrial tubes and cheap aluminum conduits, depicted with hyperrealism often striking to the eye, could be seen, at first glance, as vanitas or memento mori of our post-industrial world (in which these are progressively replaced by more ecological or digital devices and infrastructures). Either in Eastern or Western countries, these old fashioned conveyors and connectors remain in a lot of places as remnants or ruins of an almost vanished world (behind the walls, upon the ceilings and up on the roofs); that of the fossil energies and also of the omnipresence of cement in architecture and the everyday (hence the material and textural quality of the works which are acrylic or oil on cement-coated canvas). Irani’s paintings of twisted tubes and intertwined aluminum appear as disillusioned and sarcastic relics of the petro-modernity behind us (just like fragmentary corpses of old pipelines); but revived paradoxically in the most current and mundane infrastructures of mankind to irrigate the soil, electrify a house or basically create an economy. The energies and raw materials must be conveyed somehow, connecting onto the right networks and architecture of tubes, for a sustainable overall system. Still, Irani’s paintings seem to resist (or to be twisting) a certain capitalist realism; hyperrealism often contains a tendency to challenge the reality offered by capitalists tools of vision. These paintings celebrate non-connectedness and dysfunctionality, in a non-dramatic modality; while at the same time symbolizing the unexpected possibility to be connected to anyone or anything at any time. They do so with an outstanding love for the craft of the painter, almost in the pre-modern and traditional conception of a 19th painter. One could say if there is still a drama to be exorcised in his paintings, it could be through the “still lives” of non-ecological material, such as plastic or aluminum items disseminated in his works – as they are on the sea shores of our degenerated and ruined industrial landscape all around.

As Irani’s tubes always remain open and suspended in space and time (like the experience of exile), they underline a general state of non-connectedness or technological failure, seeking beauty or escape from reality, when it doesn’t seem possible anymore: each act of painting is like a cutting ties ritualistic effort which Irani doesn’t confront only on canvas (using a kind of anti-aesthetic material that is the cement) but also in three-dimensional form. His sculptures have a performative appeal for the viewer “conveyed” by their awkward orientations and open mouths.

The variety of positions and combinations between Irani’s twisted tubes takes the viewer into a playful mental labyrinth: ironically tied to each other, making funny couples, combining fragmentary elements into one sole tube (playing with itself). They reveal an artist with a mathematical sense of humor, keen to entertain our flickering eye in the paths-that-lead-nowhere; or somewhere close to an iconoclastic pink neon light or painterly aura, enhancing their orientation of “suburban art” and “post-internet abstraction” (paradoxically to their figurative virtue).

Written by: Morad Montazami, director of Zamân Books & Curating

For more information, please contact info@hamzianpourandkia.com or call (917) 751 8893.

5225 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 212, Los Angeles, CA 90036

hamzianpourandkia.com

Artists

- Kaveh Iranbi